Q&A

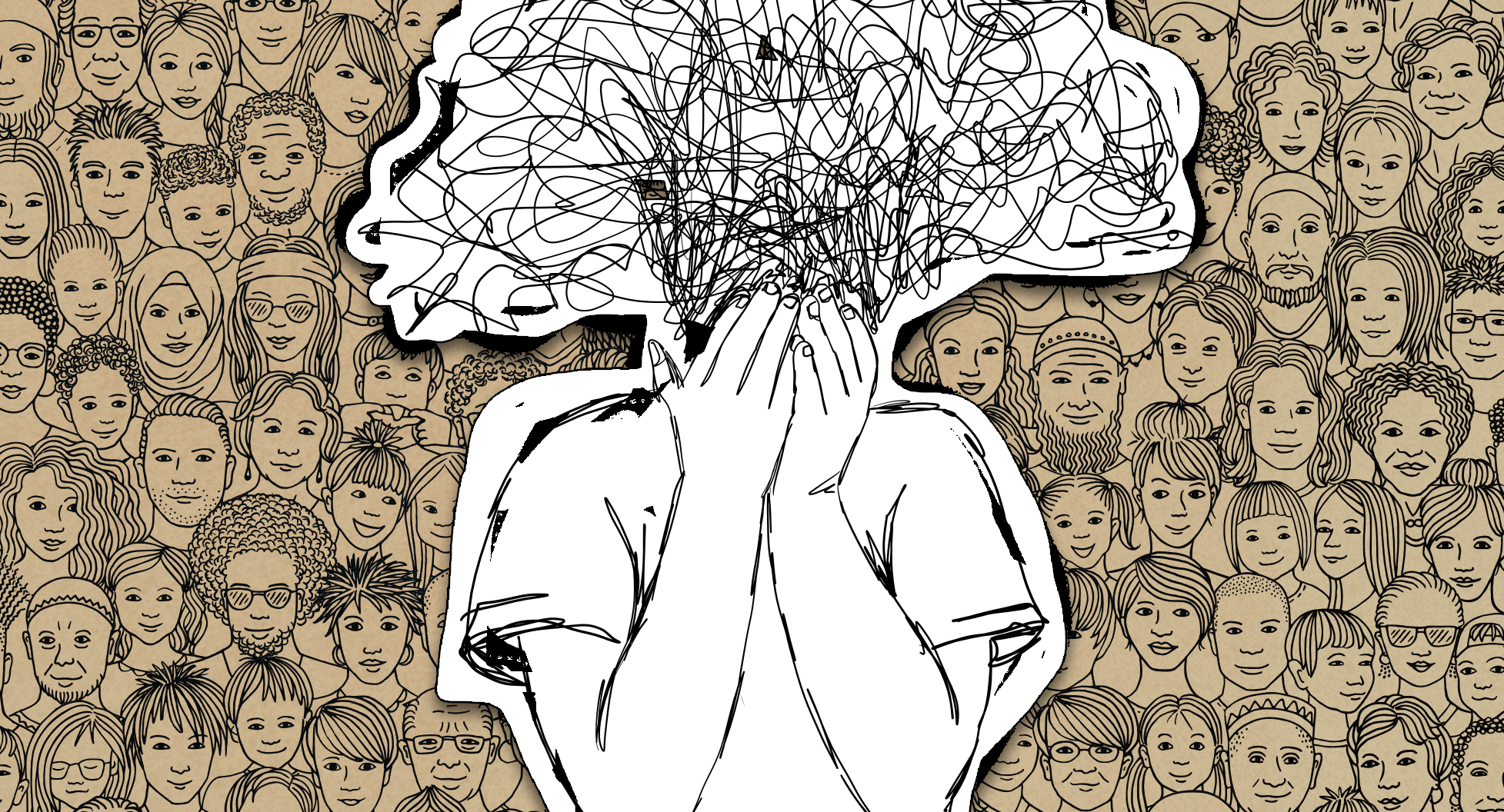

Cultural Variables within CBT

World-leading CBT expert and performance mentor Kevin Chapman answers questions on the importance of cultural awareness when treating clients.

Q

Can you give an example of how anxiety can look or present differently depending on someone's racial or ethnic background?

A pdf

pdf pdf

pdf pdf

pdf

pdf

pdfWilliams_CrossCulturalOCD_2017

pdf

pdfChapman_SAD-1_2013

pdf

pdfChapman_SAD-2_2013

Q

Is it advisable for clients to seek out therapists who have a similar racial identity as they do?

A

Q

I am aware that a key part of treatment for anxiety is learning safety but that this can be hard for people who experience a pervasive sense of unsafety based on their race or identity. Can you give me a brief outline of what anti-racist CBT looks like and how I can be more aware?

A

Q

I work with Asian Americans in NYC where anti-Asian violence has been increasingly rampant. I myself am Asian and also have anxieties about going outside. How can I address this with my clients who are limiting their lives as a result?

A

Q

How can I make culturally sensitive adaptations to CBT for youth in marginal communities with social anxiety disorder? Thanks

A pdf

pdf pdf

pdf

pdf

pdfChapman_SAD-1_2013

pdf

pdfChapman_SAD-2_2013

You may also like